The young Sufi Muslim’s ‘blasphemous’ WhatsApp message sparks an international outcry

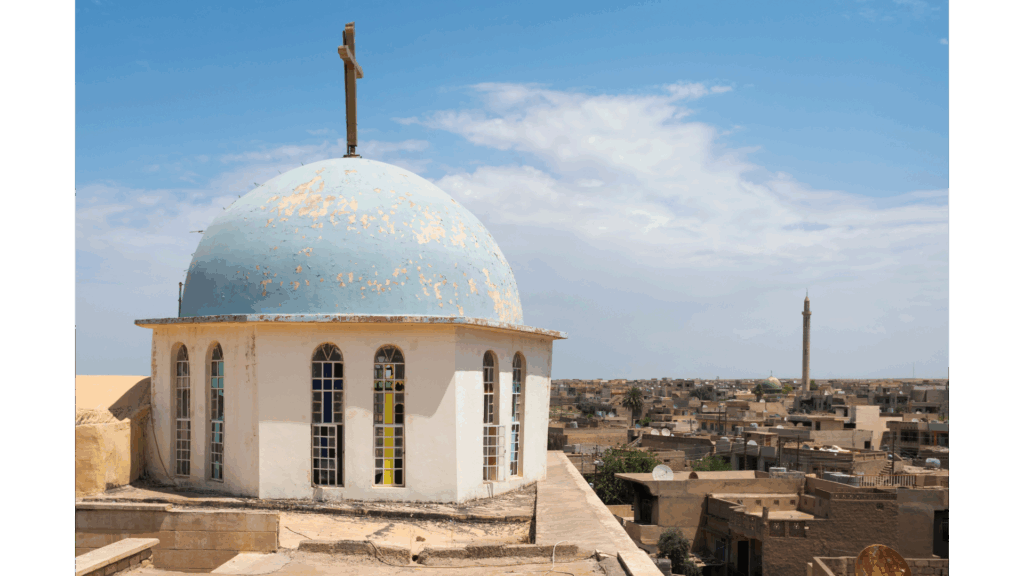

Continue readingWhat Can We Learn from Iraqi Christians 11 Years After ISIS’s Attack?

A Legacy of Faith Under Fire for Iraqi Christians

In August 2014, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) — an extremist Sunni group — launched a violent campaign across northern Iraq. Their target: Qaraqosh, an ancient Christian city located in the Nineveh Plains.

What followed became one of the most devastating assaults on religious minorities in modern Iraqi history. Now, eleven years later, the story of Iraq’s largest Christian community is far from over, and far from hopeless.

At ADF International, we’re standing alongside Iraq’s Christians, advocating for their right to worship freely and raising global awareness of their struggle.

Christianity’s Deep Roots in Iraq

Christianity is not foreign to Iraq — it’s foundational. Long before ISIS and Islam, Christianity had already taken root in Iraq. In fact, Christianity has existed in Iraq since the first century AD, long before it reached many parts of Europe.

This makes Iraq home to some of the oldest Christian communities in the world.

The Assyrian Church of the East, the Chaldean Catholic Church, and the Syriac Orthodox Church all trace their lineage to Iraq. These churches preserve early liturgical traditions and still conduct services in Syriac, a dialect of Aramaic — the language spoken by Jesus.

Many Iraqi Christians today are ethnic Assyrians, descendants of the ancient Assyrian Empire, which once ruled over much of the Middle East. Christianity became embedded in Assyrian identity after their conversion in the first few centuries AD, blending ancient cultural heritage with deep Christian faith.

Just south of the Nineveh Plains lies the region of southern Mesopotamia, where the ancient city of Ur — the birthplace of Abraham, the patriarch through whom God’s redemptive promises and Jesus flow — is located.

This land is steeped in sacred history. But history alone has not guaranteed safety for Iraq’s Christians.

The 2014 Genocide: What Happened to Iraqi Christians

In the 2014 attack, ISIS aimed to establish a caliphate in northern Iraq, one free of Christians, Yazidis, and other minorities. Qaraqosh, the largest Christian city in Iraq, was one of its primary targets.

The violence extended far beyond Qaraqosh. Sinjar, the heartland of the Yazidi people, and Mosul, once a city of rich religious diversity, were left shattered under the same campaign of destruction.

Entire villages were emptied. Ancient Christian manuscripts and artifacts were destroyed or sold on the black market. Communities that had existed for nearly 2,000 years were uprooted in a matter of days.

The assault was systematic:

- Churches and monasteries were burned, bombed, or turned into prisons and weapons depots.

- Christian symbols — crosses, icons, statues — were desecrated or publicly destroyed.

- Homes and businesses were looted and marked with the Arabic letter “ن” (nūn), short for Nasrani (Christian), a brand of targeted extermination.

- Graves and cemeteries were desecrated in an attempt to erase memory itself.

Christians and Yazidis were given four choices: convert to Islam, pay the jizya — a humiliating religious tax imposed on non-Muslims under extremist rule — flee, or die. Nearly 80,000 Christians fled their homes in a desperate exodus.

Women and Children: The Most Vulnerable

Women and girls, especially from Yazidi and Christian communities, suffered some of the worst atrocities. ISIS ran an organized network of slave markets where girls, some as young as nine, were bought, sold, and passed between fighters.

Over 6,800 Yazidi women and children were abducted, according to UN reports, and an unknown number of Christian girls were subjected to similar fates. Many have never been found.

In the chaos, tens of thousands sought refuge in the Kurdistan Region, where the regional government, while limited in resources, opened its borders. Most found shelter in refugee camps, unfinished buildings, or makeshift settlements. For many, those “temporary” shelters have now become permanent.

The Lasting Impact of ISIS’s Attack

Before ISIS’s brutal campaign, an estimated 350,000 Christians lived in Iraq. Today, that number has dwindled significantly.

As of 2024, it’s estimated that less than half of the original Christians who fled the Plains have returned. Security concerns, economic hardship, and limited infrastructure continue to hinder full resettlement.

Many Iraqi Christians remain uncertain about their ability to live openly and safely as Christians in their own homeland.

To defend themselves, locals formed the Nineveh Plains Protection Unit (NPU), a militia dedicated to defending their communities. By 2017, a coalition of Iraqi forces, Kurdish Peshmerga, local militias, and US-led air support liberated the region.

While ISIS may no longer control the region, Christians in Iraq continue to face:

- Discrimination in law and daily life.

- Threats and intimidation from militias and extremist groups.

- Barriers to reclaiming stolen homes and properties.

- Government failure to protect religious minorities.

- A lack of legal recognition and representation.

These ongoing struggles reveal a deeper truth: Iraq’s legal system, still fragile after decades of conflict, has yet to prove it will uphold the rights of Iraqi Christians.

A Visit to Qaraqosh: Seeing the Present Reality

In 2021, Pope Francis visited Iraq, including Qaraqosh, bringing global attention to the plight of Iraqi Christians. His message was clear: Iraqi Christians are not forgotten.

Earlier this year, Sean Nelson, ADF International’s Legal Counsel for Global Religious Freedom, visited Qaraqosh and the surrounding areas.

Amidst ruined buildings and ongoing hardships, Sean met determined individuals working to rebuild homes, reopen churches, and restore dignity to daily life.

What Nelson Experienced

“What I saw in Qaraqosh was Christians deeply committed to rebuilding their lives and their communities after the horror of ISIS. Many churches had been renovated and restored, and one church that was over 1000 years old, but had been left in ruins for a century, had been completely rebuilt after ISIS. Crosses were proudly displayed. And the communities were committed to never forgetting what ISIS had done. Each church still had memorials and sections showing the devastation.

“Still, these communities have seen their populations cut in half since before ISIS. Religious leaders mentioned illegal and dubious encroachments on land, and a lack of political representation and economic development. They were unanimously concerned that the Iranian-backed militias surrounding them were preventing them from being fully included as members of Iraqi society.

“I saw children playing outside one church whose families had secretly converted to Christianity. They could not visit Christian services openly out of fear of violent reprisals. The religious leaders worried that if things did not change, so many people would leave and never return. They saw sustained international pressure as one of their only hopes for most Christians to be able to remain.

“In nearby Erbil, within the autonomous Kurdistan region, where many Christians fled during the ISIS attacks, Christians are able to live relatively free lives, and the local government respects them more and celebrates the religious diversity and history of the area. They still face some hardships —particularly converts from Islam, who face violent threats — but in general, there was a more inclusive vision for Christians. That same kind of inclusion should be available to Christians in the Nineveh Plains and throughout Iraq.”

Though the situation in Iraq is slowly changing, the threat to Christian communities remains a pressing concern in Iraq and beyond.

ISIS Elsewhere

Although ISIS has waned as a threat in Iraq, its influence is spreading across the Middle East and Africa. The Middle East Media Research Institute (MEMRI), a Washington, DC-based counterterrorism research group, warns of what it calls a “silent genocide” targeting Christians.

In 2025

According to MEMRI, the Islamic State Mozambique Province (ISMP) recently published 20 images celebrating four separate strikes on Christian villages in the Chiure district of Mozambique’s northern Cabo Delgado province.

The photographs depict ISIS fighters storming villages, setting fire to a church, and destroying homes. The photographs also include scenes of the beheading of a person described by the extremists as belonging to “infidel militias,” along with two Christian civilians. Additional photographs, MEMRI’s review noted, show the bodies of several people identified by the group as members of these so-called militias.

In recent weeks, Islamic State affiliates have also claimed responsibility for killing dozens of Christians during a Catholic vigil in Komanda, DRC, and for bombing the Mar Elias Church in Damascus, Syria, which killed 20 plus Christians and injured 60.

Conclusion: The Road Ahead Requires Standing for Religious Freedom in Iraq

World leaders and international institutions must urgently unite behind a clear and effective strategy to dismantle the Islamic State network before more lives are lost.

Freedom of belief and religion is a fundamental human right. We at ADF International remain committed to defending this right for Christians around the world. We are standing with them, advocating for them, and praying for a future where they can thrive in the land their ancestors have called home for centuries.

We will continue to:

- Advocate for legal protections for religious minorities in Iraq and elsewhere

- Support survivors in their fight to rebuild lives

- Raise global awareness through policy engagement and media

- Pray for a future where faith can flourish without fear

Every day that goes by without bold action puts more lives in danger. We must act now — and we are.

Life at Risk: A Defining Week for the UK

In the span of just five days, the British Parliament took two deeply troubling steps that threaten serious consequences for the legal protection of human life.

On Tuesday, 17 June, Members of Parliament (MPs) voted 379 to 137 to decriminalise abortion — removing all criminal penalties for women who end their pregnancies at any stage. This decision eliminates essential legal protections for both mothers and babies, including for dangerous at-home abortions that take the lives of fully viable babies up to birth.

Just three days later, on Friday, 20 June, MPs also voted to move forward with a bill that would legalise assisted suicide for terminally ill patients, empowering doctors to prescribe lethal drugs to those deemed to have less than six months to live.

Together, these decisions send a deeply unsettling message: that life is only worth protecting when it is considered supposedly healthy, wanted, or useful.

Abortion Up to Birth — After Just Two Hours of Debate

The vote to decriminalise abortion took place with only two hours of debate — despite the sweeping implications of the proposal.

While current UK law already allows abortion beyond 24 weeks in a range of broadly defined circumstances, this amendment removed critical legal protections for viable babies in the womb and for women in difficult situations.

Supporters presented the move as an act of compassion toward women, but in reality, only 1% of British women support abortion until birth.

What the law now permits is not just rare: it is extreme. It removes protections that help prevent dangerous, self-managed, late-term abortions and leaves women to face serious risks alone, often in desperation.

This is not compassion. It is abandonment.

Assisted Suicide: A Dangerous Precedent

The bill to legalise assisted suicide follows the same deeply flawed logic. If passed, it will enshrine into law the false logic that ending a life can be an acceptable form of care. While its advocates insist it will be accompanied by “safeguards,” evidence from other countries tells a different story.

Take Canada, for example. Less than ten years after assisted suicide became legal, it now accounts for 4% of all deaths nationwide — a figure that continues to climb. Vulnerable people, especially those who are elderly or disabled, report feeling pressured toward death when what they truly need is support, dignity, and community.

Once a healthcare system begins to treat death as a solution, it becomes the cheaper, easier, and ultimately, default response.

A Culture of Abandonment — Not Autonomy

Both the abortion amendment and the assisted suicide bill were framed as measures that expand personal freedom. But in truth, they represent a profound abandonment — wrapped in the language of choice.

When the law permits abortion at 35 weeks, or offers lethal drugs in place of palliative care, it tells society that life is no longer sacred. Instead, the right to life is treated as negotiable — granted only to those society deems worthy.

A Better Vision for Britain

But this is not the only way forward.

There is another Britain — one that values every human life, from the youngest child in the womb to the most fragile person nearing life’s end. It is a Britain shaped by the truth that every person bears God’s image and possesses inherent dignity.

Both measures now go to the House of Lords. While the abortion amendment cannot be fully blocked, it can still be challenged and delayed. The assisted suicide bill, meanwhile, faces opposition from many peers who have pledged to resist its advance.

The Lords must give these bills the scrutiny they lacked in the Commons — and ask the hard questions others ignored.

This is a moment that calls for moral clarity. For people of faith to respond — not only in Parliament, but in practice. By supporting mothers in crisis. By walking with the dying. By upholding the dignity of the disabled. And by telling a different story: that every life is a gift, and that no one is beyond the reach of love.

Britain is facing a crossroads. And now, more than ever, we must have the courage to say no to death — and yes to life, in every stage, and every circumstance.

Europe’s Free Speech Crisis Is Making International Headlines

Imagine a Europe where quoting the Bible lands you in court. Where praying silently or offering consensual conversation on a public streetside lands you with a criminal charge and hefty fines.

Continue readingWhy Christians Face Persecution in Egypt and How There’s Hope

Christians in Egypt are under threat in a country where 10% of the population is Christian. Our Global Religious Freedom Legal Counsel, Lizzie Francis Brink, tells the story.

Legal Counsel for Global Religious Freedom with ADF International

Scripture reminds us that persecution is part of being a Christian, but few realize the scale of it today. Around the world, 1 in 7 Christians face harassment, violence, or worse simply for their faith. In Africa, this number rises to 1 in 5.

Among the persecuted are Egypt’s Christians, who live in a land of ancient wonders and rich history—yet face daily discrimination, harsh restrictions, and constant pressure to hide their faith. Despite Egypt’s status as a cultural and historical giant in Africa, it remains an ongoing struggle for many believers.

In March, I travelled to Egypt to meet with some of these brave Christians and their dedicated lawyers. Together with allied lawyers on the ground, ADF International is committed to ensuring that our brothers and sisters in Egypt are free to live and speak the truth.

Christians in Egypt

Egypt has a population of approximately 111.2 million people. Christians make up roughly 10% of this population, making them the largest Christian minority in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region.

Around 90% of Egyptians are Sunni Muslims, making Islam the dominant religion. According to Article 2 of Egypt’s Constitution, Islam is the official state religion, and the principles of Sharia Law serve as the primary source of legislation in the country.

While Article 64 of the Egyptian Constitution guarantees “absolute” freedom of religion or belief, this right is restricted in practice. Only followers of the three recognized “heavenly religions”—Islam, Christianity, and Judaism—are legally allowed to practice their faith and build houses of worship publicly.

Additionally, Article 53 of the Egyptian Constitution protects against discrimination based on religion.

But despite Egypt’s constitutional guarantees, Christians and other minority religious groups in Egypt regularly face religious freedom violations. Discriminatory practices and laws continue to restrict the ability of Christians, Shia Muslims, Ahmadis, and other non-Sunni or non-state-sanctioned Muslim groups, along with non-Muslim communities, to express and practice their beliefs freely.

The southern part of Egypt is particularly dangerous for Christians. It is more Islamically conservative than the north and heavily influenced by Islamic extremist groups. The Salafi al-Nour party, which operates legally despite constitutional bans, thrives in these underdeveloped regions, fuelling hostility toward Christians.

The Reality of Christian Persecution in Egypt

In Egypt, most persecution against Christians happens at the community level, especially in rural areas. Christian women are harassed, children are bullied in schools, employment discrimination is common, and false accusations of blasphemy often trigger violent mob attacks. These incidents force entire Christian families to flee their homes in fear.

In more extreme cases in the past, churches have been bombed, leaving dozens dead or injured. Christian women and girls have been targeted for abduction, forced conversion, and sexual violence.

While Egyptian President el-Sisi often calls for unity and support for Christians, progress on the ground remains slow. Local authorities often overlook attacks and rarely offer protection, particularly in the south. This means that challenging religious freedom injustices can also pose risks to personal safety.

Christians also face countless obstacles in building or repairing churches. Despite government promises to legalize more churches and build new ones, Christians struggle to find safe and legal places of worship. Hostile neighbours and violent mobs often stand in the way.

Converts from Islam face even greater persecution. Many are ostracized, disowned by their families, or pressured to return to Islam. State security forces monitor, intimidate, and sometimes detain converts, silencing any attempt to openly practice their Christian faith. Egyptian law makes it nearly impossible to officially change one’s religion from Islam.

Christians also face significant human rights challenges at the institutional level. Egypt’s blasphemy laws are often used to unjustly prosecute people for actions or statements deemed offensive to the dominant religion. Penalties range from hefty fines to prison sentences and, in extreme cases, death sentences.

Egypt’s International Promises and Rights Violations

Egypt has signed global treaties that promise to protect basic human rights. These include:

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)

- International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR)

- Convention Against Torture (CAT)

- Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW)

- Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC)

However, the reality on the ground often results in Egypt falling short of these obligations, especially when it comes to Christians:

- Violence against Christians goes unpunished (ICCPR Art. 2)

- Christians are unfairly accused of blasphemy (ICCPR Arts. 18 & 19)

- Children of Christian converts are forced to register as Muslim (ICCPR Art. 18, CRC Art. 14)

- Christians face job discrimination because of their faith (ICCPR Art. 26)

- Churches struggle to get building permits or legal status (ICCPR Arts. 21 & 26)

- Christian women, especially in villages, face kidnapping and forced marriage to Muslim men (ICCPR Art. 23, CEDAW Art. 16, ICESCR Art. 10)

Abdulbaqi Abdo

ADF International has been supporting the legal defence of Abdulbaqi Saeed Abdo, a Yemeni-born Christian convert and victim of religious persecution in Egypt.

In 2021, Egyptian authorities arrested him for his involvement in a private Facebook group supporting Muslims who converted to Christianity. Officials falsely accused him of “joining a terrorist group with knowledge of its purposes” and “contempt of the Islamic religion.”

For over three years, Abdulbaqi was moved between several detention and terrorism centres, subjected to terrible conditions that impacted his health. He was also repeatedly denied private family visits and access to his legal team, cutting off his ability to receive basic supplies or confidential legal support.

In August last year, Abdulbaqi sent a heartbreaking letter to his family, announcing plans to begin a hunger strike due to the ongoing injustice. He said he would refuse medical care and eventually stop eating altogether.

After years of national and international advocacy, we helped secure his release by working closely with his lawyers and raising his case before the United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention and other global religious freedom experts. We argued that Egypt violated his rights to religious freedom and a fair trial.

Thanks to this combined international effort, Abdulbaqi was freed in January this year and reunited with his family. He is now safe in another country, and we continue to support him as his case remains open.

Egypt’s Online Cybercrime and Blasphemy Laws

Under Egypt’s Cybercrime Law (175/2018), people have been investigated, arrested, and prosecuted simply for expressing their beliefs online.

Article 25 bans using technology to “violate family principles or values in Egyptian society.” This vague wording gives authorities sweeping power to censor online content and criminalize peaceful religious discussions or faith-based content on social media.

At the same time, Article 98(f) of Egypt’s Penal Code criminalizes “insulting the three heavenly religions”, though it is most often used against criticisms of Islam.

Despite international pressure to end violations of freedom of religion and speech, Egypt has shown no real effort to reform or repel these laws. Instead, religious minorities continue to be targeted.

The combination of laws designed to control terrorist activity and restrict free speech in Egypt was used to justify the arbitrary detention of Abdulbaqi for over three years.

Abdulbaqi’s case is just one of various examples of persecution faced by Christians in Egypt and across Africa.

My Trip to Egypt

ADF International has been actively involved in litigation and legal advocacy in Egypt for several years, defending religious freedom and supporting Christians facing persecution.

During my trip to Egypt, I met with the Christians we defend. I listened to their stories and saw firsthand how our alliance is standing alongside them as they fight for their right to live and worship freely.

I reconnected with our dedicated network of human rights lawyers—courageous defenders working in a country where laws are often misused to suppress religious expression. It was inspiring to strengthen these partnerships and establish new connections with Christian ministries supporting those who live out their faith.

I had the privilege of meeting Mr. Emad Felix, Abdulbaqi’s primary advocate. Mr. Felix supported the Abdo family from the start of Abdulbaqi’s detention in 2021. He has visited the court every few months since his incarceration to plead that he be released. His dedication exemplifies the vital role local lawyers play in defending religious freedom.

Our ability to engage in these critical cases would not be possible without such committed partners. We are grateful for the strong working relationship we have with lawyers in Egypt and remain committed to supporting them as they take on more cases to defend the fundamental Christian freedoms that are so often taken for granted in the West.

Conclusion: Religious Freedom is Severely Restricted in Egypt, but There is Hope

Egypt’s Christians live under constant pressure—from discriminatory laws, violent attacks, and systemic injustice. Despite constitutional promises and international treaties meant to protect religious freedom, the reality presents critical challenges.

Yet, in the face of such hardship, the courage and resilience of Egypt’s Christian community are a powerful testament to the enduring hope of the Gospel. During my trip, I witnessed that hope firsthand.

At ADF International, we are deeply committed to this fight. Our work in Egypt, alongside courageous local partners, is just one part of our broader mission to defend Christians wherever they are persecuted and to hold countries accountable to their human rights obligations.

Abdulbaqi’s release is a clear example that our efforts, combined with international pressure and prayer, can bring real change—and we’ve seen similar breakthroughs elsewhere in Africa and beyond.

While the road ahead is long, we remain steadfast. The Gospel continues to shine brightest where darkness tries its hardest to overcome it. Together, we will keep standing with Egypt’s Christians until the promise of true religious freedom becomes reality.

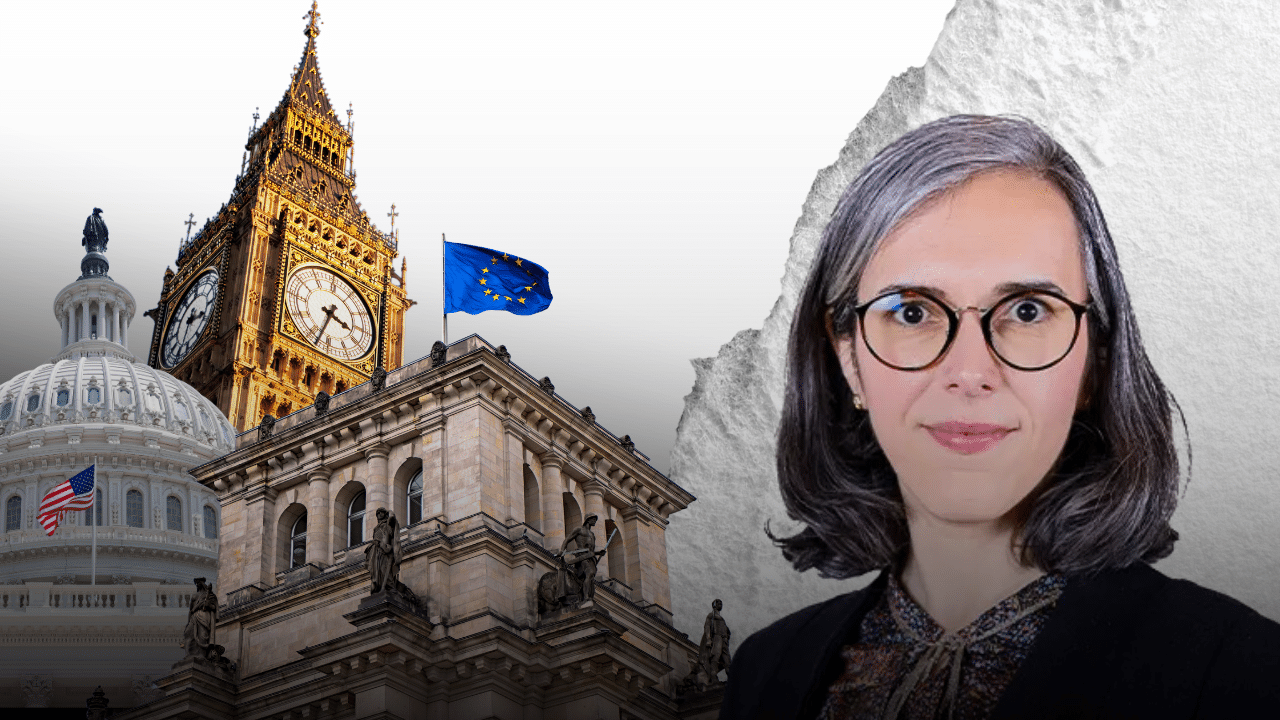

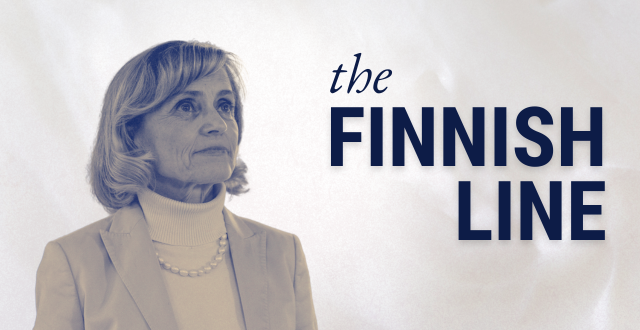

The Finnish Line: The Supreme Case of Päivi Räsänen After 6 Years

A Nation Watches as One of Its Most Respected Leaders Goes to the Supreme Court for Speaking Her Faith

Update Sept. 2025: The Finnish Supreme Court has set the date for an oral hearing on 30th October 2025.

The case of Finnish MP Päivi Räsänen is more than a legal battle; it’s a test of Europe’s commitment to democratic values.

As one of Finland’s most respected politicians, Päivi now faces the Finnish Supreme Court for peacefully expressing her Christian beliefs online.

Her story is a powerful reminder of what it means to be a Christian in today’s pervasive culture of censorship. It also demonstrates unwavering faith in the face of prosecution and punishment for so-called “hate speech”.

ADF International is proud to stand alongside Päivi as her legal ordeal reaches its 6th year.

A Life of Conviction

Päivi was still a very young girl when her parents decided she could go to the church in their small village of Konnunsuo, just inside the Finnish border from Russia. It’s a region known for hundreds of beautiful lakes and one less beautiful prison, where Päivi’s father worked, tending the gardens. While he and his wife were not Christians, they respected the faith and didn’t feel it would do little Päivi any harm to learn a bit of the Bible.

Time would prove them both wrong and right about that, but as a child, Päivi was fascinated with the things she learned in those Sunday morning classes.

“It was very, very affecting and important for me,” she remembers, nearly six decades later. “I was about 5 or 6 years old, and I remember well, even at that age, those talks the teachers shared with us about Jesus.”

Biblical concepts like grace and sin, salvation and judgment, she says, “were so concrete. Even as a small child, you have to think about these issues. And I remember praying that I would have my sins forgiven, and that Jesus would come into my life.”

How seriously Päivi took her new conversion became clear shortly afterward, when the prison warden came riding along the road by her family’s house on his bicycle. She urgently waved for him to stop. He did, looking down into her big, earnest, little-girl eyes to ask what was wrong.

“Do you love Jesus?” she asked. “You can’t get to heaven if you do not know Him.”

Embarrassed, the warden looked around and saw Päivi’s mother, standing nearby. “You should take your baby out of that Sunday school today!” he yelled. “Before she loses her mind!”

If her mother was concerned about her husband’s boss’s opinion, she didn’t show it. Päivi stayed in Sunday school. But it was by no means the last time Päivi spoke up for her faith. Or drew sharp opposition for doing so.

The Start of Päivi’s Career

Although she went to the University of Helsinki to study medicine, Päivi spent at least as much time there sharing her faith. For five years, she led a student missionary group in weekly door-to-door visits around campus, drawing other young people into discussions about moral values and cheerfully engaging them with the Gospel of Jesus Christ.

“It was an important time in my life,” she remembers, “an important schooling. Every week, I was discussing quite difficult issues with students from different backgrounds and areas of study. I had to think very thoroughly about how my faith stands — how the Bible stands — in the face of these difficult questions. I learned to discuss ideas. I learned to debate.”

Her extracurricular evangelism also changed her life in another way. Twice during those years, Päivi joined other Christian students from all over Finland on mission trips to London, led by a tall, smiling young man named Niilo Räsänen.

He and Päivi took a shine to each other, began to date, and soon were married. They went on to raise four daughters and a son, as Niilo became a pastor in the Evangelical Lutheran Church and head of one of the denomination’s seminaries.

Päivi, meanwhile, went into general practice medicine. She quickly developed a reputation as both an excellent doctor and a thoughtful, outspoken defender of life.

“I had decided already during my studies that I would not end the life of a child in the womb,” she says. In her spare time, she wrote books and pamphlets on the subject. That led to television and radio appearances, where she drew on those debate skills she’d honed back in college. Her strong, winsome arguments began to attract wide attention. People asked if she was interested in standing for office — perhaps campaigning for a seat in Parliament.

“At first I refused,” she says. “I thought it was not my place.” But people continued to urge her to run … and one of those urging was her husband.

“Actually, I think I was the first,” Niilo says. “But she wasn’t interested.” One day, though, he drove her through Helsinki, past the building where Parliament met. He pointed at the building. “Look at your future workplace,” he told her.

The 1990s brought a severe economic recession to Finland. Päivi’s patients were hit hard by what was happening and often poured out their worries to her.

“I could see a lot of problems in people’s lives,” she says — problems born of what was happening in her country’s politics and culture. “I thought I would like to try and influence the society and improve the welfare of the people. To not only give them medicine, but to try to heal the consequences of these problems.”

A person in Parliament could do that, she decided. The next time someone suggested she stand for office, Päivi was ready. “I answered, ‘Yes.’”

Päivi as a Parliamentarian

Päivi Räsänen has served continually in the Finnish Parliament since 1995. For 11 of those years, she acted as chairman of the Christian Democrats, a party she chose for its support of her Christian values and unswerving opposition to abortion. For four years, she also served as her nation’s minister of the interior, overseeing internal national security and migration issues.

“I have felt, very deeply, that this has been my calling,” she says. “I’ve been happy to have the opportunity to influence our society, our country, and to try to make better living conditions for people, especially families and children and the elderly.

“In some ways, it is very similar to working as a doctor. People come to you to talk about their problems, and then you try to find some solution. That’s been my work in Parliament.” She’s learned, she says, that “politics is one way to show love to your neighbour.”

You might think that attitude would have enhanced Päivi’s interactions with Finland’s religious leaders — “church affairs” was another aspect of her responsibilities as minister of the interior, and her work brought her into contact with most of the prominent clerics of her country.

Still, even knowing these leaders so well, she was stunned to learn, in the summer of 2019, that the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland — her own denomination and the one in which her husband served as a pastor — had pledged its full support for an upcoming Helsinki Pride event.

“I knew that our church at that time was already quite divided,” Päivi says, “and there was a lot of progressive liberal thinking among our pastors.” Still, “that the whole church leadership had decided to support the event, publicly and financially, was a strong disappointment to me — and to many other Christians.”

Many friends confided to her their intention to resign from the church. Päivi seriously considered joining them. “I was praying, ‘What should I do now? Should I leave the church, too?’”

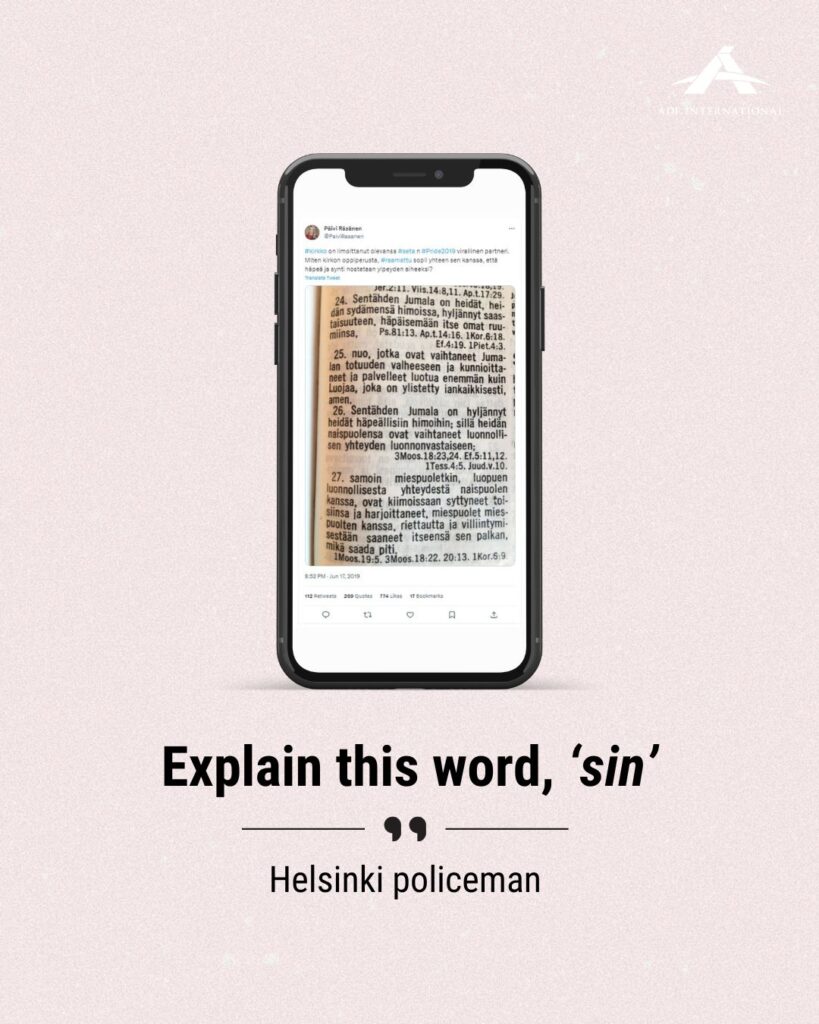

The Tweet That Sparked a Trial

But, on her knees, her Bible open before her, “I received a very clear vision,” Päivi says, “that now was not my time to jump out of this sinking boat — that I should try to wake people up. I was especially worried about our young people losing their trust in the Bible, with the leadership of the church teaching something so much against what the Bible teaches.”

“What the Bible teaches.” After a moment, she reached for her cell phone, turned to Romans 1:24-27, and snapped a photo. She pulled up her X (formerly Twitter) account, attached the picture, called it to the attention of the Evangelical Lutheran leadership, and added one simple question:

“How does the doctrine of the church, the Bible, fit together with the fact that shame and sin are raised as a matter of pride?”

She pressed “Tweet.”

And her life changed, forever.

Päivi’s communique thoroughly rocked “the boat” and woke up everyone in it. Including Päivi.

A few weeks after she had posted the tweet, she opened a newspaper and read — to her astonishment — that local police had received a complaint about her message and were investigating. Their evidence would determine whether the nation’s chief prosecutor would bring her to trial for her beliefs.

“At first, I didn’t believe it,” Päivi says. “I thought, ‘No, no, this must be from a summer intern who doesn’t know what he’s saying.’” But a call to her local precinct confirmed that officers were indeed looking into the matter. When could she come in and speak with them?

Over the next few months, Päivi would be required to sit for a total of 13 hours of police interrogation.

“It was an absurd situation,” she remembers, “sitting there in a small room in the station, being interrogated about my Christian beliefs.” The policeman asking questions kept an open Bible on the table between them. He pointed at it as he probed her theology: “What is Romans about?” “Tell me about the first chapter.” “Walk me through Genesis.” “Explain this word, ‘sin.’”

Päivi found the whole thing almost laughable. “Just a few years before, I was the [cabinet] minister in charge of police, and now I was sitting here, being interrogated.” But the people of Finland understood what was happening: one of the most well-known political figures in their country was being detained at police headquarters for quoting Scripture to bishops.

“Someone joked on social media that maybe we were going to have Bible studies at the police station,” Päivi says, smiling. “But … these discussions were very good. I had the opportunity to [share with] that policeman very thoroughly the teachings of the Bible, from Genesis to the message of the Gospel … because he asked me to.

“Do you really want to hear this?” she asked him. “Because this has been such an important book to me. When I read it, I understand the message of the Gospel: that Jesus has died for my sins.”

“It was lovely,” she says, smiling, “telling that to the policeman.”

She left an impression. “If it were up to me,” he told her, after their last discussion, “you wouldn’t be sitting here. I hope we don’t have to meet like this again.”

Charged With “Hate Speech”

They didn’t. But Päivi had to wait more than a year to learn that the Finnish prosecutor general was formally charging her with three counts of “agitation against a minority group” — one, for publicly voicing her opinion on marriage and human sexuality in a 2004 pamphlet distributed at her church; two, for comments she made on the same topics on a 2019 radio show; and three, for the tweet directed at the leadership of her church.

Under Finland’s criminal code, “agitation against a minority group” falls under the section of “war crimes and crimes against humanity” punishable by tens of thousands of dollars in fines — and up to two years in prison.

Päivi knows better than most the penalty for breaking this particular law. After all, she was a member of the Finnish Parliament when it unanimously adopted these changes to the country’s criminal code 13 years ago.

“In Finland, as in all European countries, you have a law that prohibits so-called ‘hate speech,’” says Elyssa Koren, legal communications director for ADF International. Like most such laws, she says, this one carries with it the possibility of criminal charges. That’s not all the laws have in common.

These laws are often presented, Koren says, as a way “to reduce social tensions, to curb hostility, to foster conditions of peace. It’s a very reductive way of looking at societal problems … the idea that if you have less ‘hate speech,’ you’ll have less hate.” Unfortunately, she says, the laws are also “vaguely worded, overly broad, and don’t define ‘hate.’”

“‘Hate,’ really, is just in the eye of the beholder,” she says. “And what happens is what we’ve seen with this case: people are prosecuted for perfectly peaceful expression in the name of preventing ‘hate.’” When the law was passed in the Finnish Parliament, “nobody was much aware what the consequences would be. Päivi’s case is the litmus test for how the law will be applied to religious speech.”

Päivi says she sees now that she and her colleagues underestimated the implications of the law they all voted for. Many serving with her in the Finnish Parliament, she says, believe that “if I were to be convicted, then we would have to change the law.

“I’m not the only one in Finland who has spoken and taught about these issues,” she says. “There are thousands and thousands of similar writings. If my writings are banned, then [many] sermons and interviews and writings would be in danger. If I were convicted, it really would start a time of persecution among Christians.”

Which, unfortunately, seems to be the idea.

“‘Hate,’ really, is just in the eye of the beholder.”

Päivi Räsänen

Faith Under Fire

Päivi and her co-defendant — Bishop Juhana Pohjola, who is charged with publishing the 2004 pamphlet on marriage and sexuality Päivi shared with her church — were stunned when the prosecutor opened her case against them by showing Bible verses on a courtroom screen. Her ignorance of Christian theology was palpable, and she made no secret of her determination to see Päivi and Bishop Pohjola punished for views so contrary to contemporary secular morality.

“It’s become clear,” Koren says, “that they are not prosecuting Päivi Räsänen … they’re really prosecuting the Bible and Christian beliefs at a very high level. What’s at stake is the fundamental question of whether people — particularly people in the public eye — have the freedom to voice their Christian convictions in the public space.”

“What the prosecutor essentially is calling for,” says Paul Coleman, Executive Director of ADF International, “is the criminalization of the orthodox Christian position on fundamental Christian doctrine regarding marriage, sexuality, sin, and so forth. It’s shocking to see such brazen anti-Christian legal argumentation within a criminal context.”

Even more unsettling, Coleman says, is the fact that “there’s nothing unique about the situation in Finland. It doesn’t have worse law than anywhere else. It has a better legal system than most places. If this can happen in Finland, it can happen in any Western country.”

In fact, he says, “the same censorial sentiments exist in the U.S. — at all heights of power. On almost every college campus. In all of the major companies, particularly Big Tech. They exist in much of the U.S. political system and in the mindset of many law professors.

That line — between what we’re seeing take place in Finland and what could very soon happen in the U.S. — is far smaller than most people realize. Or want to admit.”

A Ruling Due Before the Supreme Court

In March 2022, the Helsinki District Court unanimously acquitted Päivi and Bishop Pohjola of all charges, saying, “It is not for the district court to interpret biblical concepts.” A month later, the prosecutor appealed that ruling — something she is allowed to do under Finnish law. In November 2023, the Helsinki Court of Appeal confirmed the lower court’s acquittal.

The prosecutor then appealed both decisions to the Finnish Supreme Court, which has agreed to hear the case.

What the prosecution has secured, Koren says, “is another year or two during which Päivi is still under this pressure. Her reputation and her integrity as a civil servant are clouded by the fact that she continues to be criminally prosecuted for her peaceful expression.”

Still, Niilo says, “We don’t worry. Whatever happens, we will take it as God’s will and see what comes next.”

“It’s remarkable,” Päivi says, “how God uses this.” From the beginning, she says, “I had a deep, deep feeling this was in God’s hands, that He was opening a door. There’ve been so many opportunities to testify about Jesus … before these courts, in front of police officers, even to those who vehemently disagree with me. It’s given me a lot of joy.

“I’ve received messages from people who’ve told me that, as they’ve followed the trials and listened to my interviews, they’ve started to read the Bible and pray. They’ve found Christ.

“I got a call from a 22-year-old man who told me that he knew almost nothing about Christianity but was listening to a radio interview where I said, ‘If you want to know Jesus, you can pray, He will come into your life.’ He has been a Christian now for over two years. Jesus came into his life.”

As a lawyer who feels called to defend freedom of religion and speech,” Coleman says, “it’s been the great privilege of my career to be [able] to support and defend Päivi. I’m not exaggerating by saying she is, ultimately, the reason why we exist.

“She’s tough. Really tough. Yet … always smiling, always kind. Over the past five years, I’ve sat through two trials with her, sat around her kitchen table, seen her in every context in between. She’s just such an unbelievably authentic person. The same in every context, whether being cross-examined for her faith, or hosting us for dinner after the hearing.”

During one hearing, Coleman says, “the prosecutor — who, bear in mind, has said horrible things about her and wants to put her in jail — was visibly unwell. And, at one of the breaks, Päivi just went over to sit with her, ask how she was doing, connect with her on a human level.

“She wasn’t doing it for the cameras,” he says. “No one saw it. But I thought, ‘What a remarkable person this is.’ It’s just such a privilege to be called as a ministry to stand alongside her and say, ‘We’ve got your back.’”

“I have received much more during this legal process than I have lost,” Päivi says. “When I was young, I read from those texts where Jesus says that, when they take you in front of courts and kings, you’ll be His witness, and He will provide what to say. I could never have believed I would ever be in this kind of situation. But I think it’s increased my trust in God.

“What I’ve found is that what God has promised, He is faithful [to do]. He really works as He has said. Jesus is alive, and He stands by His word. And He is good.”

Conclusion: The Assault on Freedom of Expression

At the heart of Päivi’s case is a growing trend across Europe: the weaponization of vague and subjective “hate speech” laws to suppress peaceful expression. The implications of this case extend far beyond Finland. What does this mean for ordinary European citizens if a respected parliamentarian can be prosecuted for a tweet?

International law, and that of Finland, guarantees freedom of speech and religion, yet cases like Päivi’s show how these rights are increasingly being violated or reinterpreted to serve ideological ends. If she were to be convicted, it would mark a dangerous shift towards state control over individual freedoms.

The principle at stake is not whether one agrees with Päivi’s beliefs. It’s whether a European democracy can still allow space for diverse opinions in the public square. Once the state decides which views are acceptable and which are not, the door opens to widespread censorship.

Europe’s commitment to democracy demands better. The Finnish Supreme Court now has a decision to make, and the world is watching. Time will tell, but one thing is certain: Päivi Räsänen will not be silenced.

ADF International is honoured to stand by her side, just as we’ve done for the last six years.

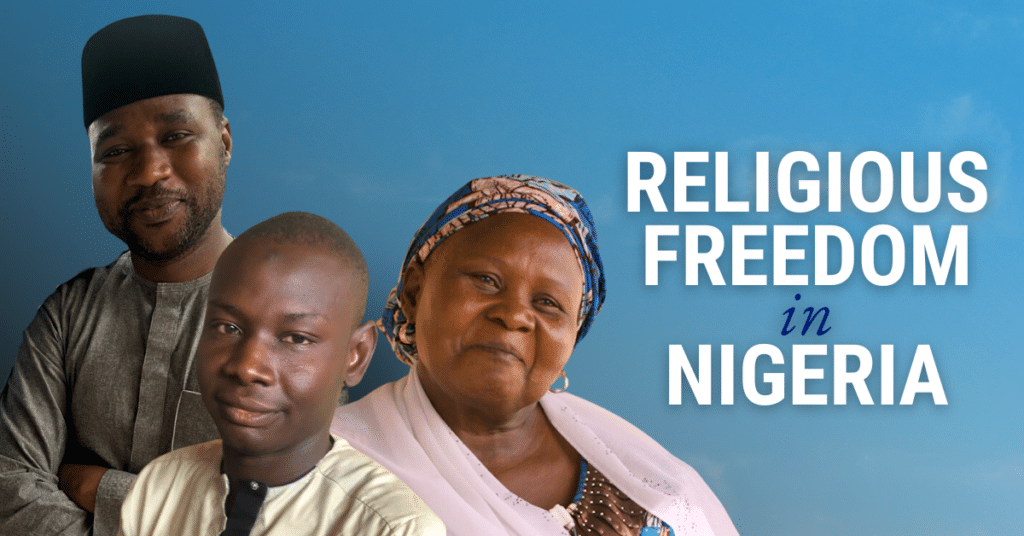

Persecution in Nigeria: Rhoda Jatau Acquitted; Mubarak Bala Released; What About Yahaya Sharif-Aminu?

Two Nigerian religious freedom prisoners were released. Yahaya Sharif-Aminu should be next

Legal Counsel for Global Religious Freedom with ADF International

Amid escalating violence and deepening insecurity, Nigeria has become one of the most dangerous countries in the world for Christians — and anyone else daring to express beliefs that deviate from the dominant religious perspective.

This reality is starkly highlighted in the cases of Mubarak Bala, Rhoda Jatau, and Yahaya Sharif-Aminu — three individuals from different religious backgrounds whose lives have been derailed by accusations of blasphemy in Northern Nigeria, a region living under sharia law.

Their experiences, along with countless other persecuted Nigerians, highlight a troubling trend: Nigeria’s blasphemy laws are weaponized to silence dissent. They enable mob violence, distort legal processes through Islamic extremism, and leave innocent individuals vulnerable to persecution simply for their beliefs or expressions.

Prisoners of Blasphemy Laws in Nigeria

Mubarak Bala, the president of the Humanist Association of Nigeria, became a target of these draconian blasphemy laws after posting on social media. What followed was swift and tragic: an arrest, public vilification, and legal charges that completely disregarded his basic rights.

Mubarak was arrested in April 2020 following complaints about posts he made on Facebook, which were deemed offensive to Islam. In 2022, he was convicted of eighteen counts related to blasphemy under Sections 210 and 114 of the Kano State Penal Code and was sentenced to twenty-four years in prison.

His supposed “crime” was speaking openly against Islamic beliefs.

His case was marred by numerous irregularities, including being detained without charges for nearly a year and a half, being denied access to legal counsel, family, and medical care, and experiencing significant delays in his trial.

After serving four and a half years in prison, Mubarak was recently released.

ADF International Cases

Our clients, Rhoda Jatau and Yahaya Sharif-Aminu have faced similar persecution.

Rhoda Jatau

Rhoda, a lifelong civil servant in Bauchi State, Nigeria, was imprisoned in 2022 for 19 months for allegedly sharing a video on WhatsApp condemning the lynching of Deborah Emmanuel Yakubu, a Nigerian student who was murdered and set on fire by a mob of her classmates for sharing her Christian faith.

As a result, Rhoda was charged with “inciting public disturbance” and “exciting contempt of religious creed” under Sections 114 and 210 of the Bauchi State Penal Code.

From the time of her arrest, Rhoda was repeatedly denied bail and detained incommunicado, only having intermittent access to legal counsel and family members during court appearances. With our support, along with allied lawyers on the ground in Nigeria, Rhoda was acquitted in December of last year. She remains in a now safe, undisclosed location.

Mubarak Bala and Rhoda Jatau’s blasphemy charges essentially functioned as sharia laws for alleged blasphemy against Islam, even though they were charged under state penal codes.

Yahaya Sharif-Aminu

Yahaya Sharif-Aminu, a young Sufi musician in Kano State, Nigeria, has faced his state’s sharia criminal laws directly. Unfortunately, Yahaya still languishes in prison.

In 2020, Yahaya was convicted and sentenced to death by hanging, despite not having legal representation, for sending song lyrics on WhatsApp that were deemed blasphemous towards the prophet Muhammad.

His conviction was overturned, and a new trial was ordered in January 2021 because of procedural irregularities in the original trial. Yahaya appealed this decision, claiming that the case should be dropped completely and that the law against blasphemy should be declared unconstitutional, but a Court of Appeal upheld the retrial order.

Yahaya has now filed an appeal with the Supreme Court of Nigeria, in the first case of its kind that could overturn the country’s death penalty blasphemy laws found in its sharia criminal codes. In the meantime, Yahaya still faces a potential death penalty.

Commonalities among Mubarak, Rhoda, and Yahaya

This trio of cases exhibits notable similarities, highlighting the pervasive nature of blasphemy laws and the extent of state overreach in enforcing them.

Mubarak, Rhoda, and Yahaya come from northern Nigeria, a predominantly Muslim region, where challenging the majority Islamic ideology often leads to severe legal and socio-cultural repercussions.

Although all three come from different religious backgrounds, each has faced persecution under the same oppressive system. Rhoda, a Christian, is a target simply because her faith conflicts with the region’s dominant ideology. Mubarak, an atheist, challenges the foundation of religious authority, placing him in direct conflict with sharia law. And Yahaya, a minority Muslim, shows that even those within Islam aren’t safe.

Online Censorship

In all three cases, the alleged “crimes” involved online or digital expressions deemed offensive by Islamic authorities. These digital acts, rooted in personal belief and freedom of expression, have been met with unjust legal and social consequences.

All three have been denied fair trials. And all three have lived in fear for their lives.

Sharia blasphemy laws function not only as a religious legal system but also as a repressive tool for controlling all forms of expression, making it one of the most severe forms of censorship.

These are only a snippet of cases highlighting Nigerian persecution. Recent reporting shows that 3,100 Christians were killed and 2,830 kidnapped in Nigeria last year, far more than in other countries in the same year. Disturbingly, the stats are believed to be higher since many cases remain unreported. One report described over 8,000 targeted killings of Christians in Nigeria in 2023.

These stats expose deeply troubling flaws within Nigeria’s justice system and raise doubts about its commitment to international human rights law and the protection of human lives.

Deborah Emmanuel’s killing in a mob attack in Sokoto State back in 2022, fuelled by strong hatred toward Christians, exemplifies the hostile socio-cultural climate of the northern region.

What Constitutes Blasphemy under Sharia Law?

Sharia law is a framework of ethical and religious principles that guides the daily lives of Muslims worldwide, including nearly 50% of Nigeria’s population. Since 1999, most northern states in Nigeria have operated under this framework.

The sharia criminal statute that Yahaya was convicted under calls for the death penalty for any Muslim who “insults” the Quran or its prophets. The non-sharia blasphemy laws call for imprisonment for so-called “religious insults” and can apply to anyone, often being used as substitute Sharia laws.

Nonetheless, Nigeria is officially a secular federation, with power divided between the national government and individual state governments. Within this structure, state governments have the power to shape their system of law so long as they adhere to the Nigerian Constitution, which is supposed to protect fundamental human rights.

The cases of Rhoda, Mubarak, and Yahaya expose glaring contradictions between sharia and blasphemy laws, and constitutional guarantees. These cases demonstrate how sharia and blasphemy laws are eroding Nigeria’s commitment to the principles enshrined in its Constitution.

Specifically, the violation of Section 38, which guarantees freedom of thought, conscience, and religion.

These cases show the urgent need to challenge these egregious laws and hold states accountable for their human rights obligations.

How Can We Free Yahaya Sharif-Aminu from Prison?

Thankfully, dedicated lawyers on the ground, working with ADF International and other advocates, are fighting for pathways to justice.

Rhoda’s acquittal and Mubarak’s release stand as powerful reminders that international pressure, human rights campaigns, and public awareness can lead to positive changes, even under the constraints of blasphemy laws.

Now, international efforts are intensifying to free Yahaya and end unjust sharia blasphemy laws once and for all.

Last year, the European Parliament overwhelmingly called for Yahaya’s immediate release, and a group of 209 international and Nigerian human rights advocates wrote to the then-Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari. In addition, the United Nations and American officials have repeatedly called for Yahaya’s immediate release and denounced his case as in violation of international law.

Yahaya’s potentially landmark Supreme Court appeal, which we are supporting, could end blasphemy laws in his home state of Kano and across northern Nigeria — a decision that could lead to the eventual abolishment of blasphemy laws around the world.

Conclusion: Rhoda and Mubarak’s Fate Should Spur Calls for Yahaya’s Release

Blasphemy laws represent a blatant breach of Nigeria’s commitments to international human rights treaties and a profound insult to the dignity and autonomy of its citizens.

If Nigeria is to emerge from this oppressive shadow, it must confront these systemic injustices and work toward a future where freedom of thought, conscience, and religion are not mere constitutional promises but lived realities for all.

We urgently call on Nigeria to spare Yahaya’s life and release him from prison. While Rhoda’s acquittal and Mubarak’s release are steps in the right direction, the fight is not finished until all are free to live and speak the truth.

How the EU Digital Services Act (DSA) Affects Online Free Speech in 2025

Nicknamed the ‘Digital Surveillance Act’, the EU’s key online platform legislation hit its one-year mark in February 2025

Senior Counsel, Europe, ADF International

The European Digital Services Act (DSA), which took effect last February, has been hailed as a landmark law designed to bring order to the digital world. Yet, beneath the surface of supposedly protecting democracy, lies a framework fraught with overreach, ambiguity, and the erosion of fundamental freedoms.

The EU Commission claims that the Digital Services Act is needed to “protect democracy” by tackling so-called “misinformation”, “disinformation” and “hate speech” online. It promises to create a safer online space by holding digital platforms—particularly “Very Large Online Platforms” (VLOPs) such as Google, Amazon, Meta and X—accountable for addressing these terms.

However, its implementation raises grave concerns. By mandating the removal of broadly defined “harmful” content, this legislation sets the stage for widespread censorship, curtailing lawful and truthful speech under the guise of compliance and safety. The result will be a sanitized and tightly controlled internet where the free exchange of ideas is stifled.

Ultimately, the EU Digital Services Act will allow the silencing of views online that are disfavoured by those in power.

Freedom of speech is the cornerstone of a democratic society and includes the right to voice unpopular or controversial opinions. For this reason, ADF International is committed to ensuring that the right to freedom of speech is firmly upheld.

The Implications on Free Speech

The Digital Services Act’s regulatory framework has profound implications for free speech.

Under the DSA, tech platforms must act against “illegal content”, removing or blocking access to such material within a certain timeframe. However, the definition of “illegal content” is notably broad, encompassing vague terms like “hate speech”—a major part of the DSA’s focus.

The DSA relies on the EU Framework Decision of 28 November 2008, which defines “hate speech” as incitement to violence or hatred against a protected group of persons or a member of such a group. This circular definition of “hate speech” as incitement to hatred is problematic because it fails to specify what “hate” entails.

Due to their vague and subjective nature, “hate speech” laws lead to inconsistent interpretation and enforcement, relying more on individual perception rather than clear, objective harm. Furthermore, the lack of a uniform definition at the EU level means that what is considered “illegal” in one country might be legal in another.

Given all this, tech platforms face the impossible task of enforcing uniform standards across the EU.

The effects of the DSA will not be confined to Europe. There are legitimate worries that the DSA could censor the speech of citizens worldwide, as tech companies may impose stricter content regulations globally to comply with European requirements.

Big Tech Platforms

Tech platforms aren’t just removing clear violations—they’ve also started removing speech that could be flagged as “harmful”. If you post a political opinion or share a tweet that some might find offensive, it might get flagged by an algorithm. To avoid massive fines or penalties, platforms will err on the side of caution and remove your post, even if it’s perfectly lawful.

Platforms rely on the automated removal of “harmful” information. These tools are widely known to be inaccurate, often fail to consider context, and therefore flag important and legal content. And if it’s not the algorithms that flag your content, it may be regular users who disagree with what you’re saying.

Alleged “Hate Speech” Case

There are many instances in which “hate speech” laws have targeted individuals for peacefully expressing their views online, even before the DSA came into effect. ADF International is supporting the legal defence of Päivi Räsänen, a Finnish Parliamentarian and grandmother of 12, who stands criminally charged for “hate speech”.

Päivi shared her faith-based views on marriage and sexual ethics in a 2019 tweet, a radio show, and in a 2004 pamphlet that she wrote for her church, centred on the Biblical text “male and female he created them”.

Päivi endured two trials and years of public scrutiny before she was unanimously acquitted of “hate speech” charges by both the Helsinki District Court and the Court of Appeal. Despite her acquittal, the state prosecutor has appealed the case, taking it to the Finnish Supreme Court.

It’s obvious that these laws aren’t only about combatting hate and violence; rather, they may target any speech deemed controversial or that challenge the status quo.

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from YouTube. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationPenalties for Non-Compliance with the EU Digital Services Act

The penalties for failing to comply with the EU Digital Services Act are severe.

Non-compliant platforms with more than 45 million active users could be fined up to 6% of their global annual turnover. For tech platforms like Google, Amazon, Meta, and X, this means billions of euros. So, even the biggest tech companies can’t afford to fall short of the DSA regulations.

If a platform repeatedly fails to comply with the DSA, the EU Commission can impose a temporary or permanent ban, which could result in the platform’s exclusion from the EU market entirely. For platforms that rely heavily on this market, this would mean losing access to one of the world’s largest digital markets.

The risks are high, and tech platforms will scramble to ensure they comply—sometimes at the expense of your fundamental right to free speech.

Section 230, the DSA, and the UK Online Safety Act

The US, the EU, and the UK take different approaches to regulating online speech. While Section 230 protects platforms from liability in the US, the Digital Services Act and the UK Online Safety Act enforce stricter content moderation rules, requiring platforms to remove “illegal” and “harmful” content or face severe penalties.

Below is a comparison of how each framework handles platform liability, free speech, and government oversight:

| Feature | USA (Section 230) | EU (Digital Sservices Act) | UK (Online Safety Act) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Legal Basis | First Amendment protects free speech; Section 230 shields platforms from liability. | EU regulation on transparency and accountability, resulting in content moderation. | UK law regulating online content to prevent harm, with strict enforcement. |

| Platform Liability | Section 230 protects platforms from liability for most user-generated content. | Large platforms must remove illegal content or face penalties. | Platforms must remove harmful but legal content or face fines. |

| "Hate Speech" | Protected unless it incites imminent violence. | Platforms must remove illegal "hate speech". | Requires platforms to remove content deemed harmful, even if legal. |

| "Misinformation" | Generally protected under free speech laws. | Platforms must take action against "systemic risks" like "disinformation". | Platforms must mitigate risks from "misinformation", especially for children. |

| Government Censorship | The government cannot censor speech except in rare cases (e.g., incitement to violence). | “Trusted flaggers” can flag content for removal, but independent oversight applies. | The regulator (Ofcom) enforces rules, and platforms must comply. |

“Shadow Content Banning”

In the digital age, we rely increasingly on digital technology to impart and receive information. And it’s essential that the free flow of information is not controlled by unaccountable gatekeepers policing what can and cannot be said.

ADF International’s stance is clear: this legislation will result in dangerous overreach that threatens the very freedoms it claims to protect.

In January, our legal team attended a plenary session and debate at the EU Parliament in Strasbourg regarding the enforcement of the DSA. The discussion brought to light significant concerns across the political spectrum about how the DSA may impact freedom of speech and expression, and rightfully so.

EU Parliament

Several members of the EU Parliament (MEPs), who initially favoured the legislation, raised serious objections to the DSA, with some calling for its revision or annulment. A significant point of contention was the potential for what they termed “shadow content banning”—removing content without adequate transparency.

This includes cases where users might be unaware of why their content was banned, on what legal basis, or how they can appeal such decisions. Most of the time, they’re left with nothing but a generic AI response and no explanation.

Some MEPs, like French MEP Virginie Joron, referred to the DSA as the “Digital Surveillance Act”.

Despite intense opposition, the EU Commission representative and the Council of the EU representative promised to enforce the DSA more rigorously. They vowed to double down on free speech by enforcing more thorough fact-checking and anti “hate speech” laws “so that “hate speech” is flagged and assessed [within] 24 hours and removed when necessary”.

They failed to provide comprehensive responses to the concerns raised about the DSA’s potential to erode fundamental rights, leaving critical questions about its implementation and implications unresolved.

Conclusion: EU Digital Services Act or “Digital Surveillance Act”?

The EU Digital Services Act’s enforcement mechanisms are riddled with ambiguity. Terms like “misinformation,” “disinformation,” and “hate speech” are too wide and vague to serve as a proper basis for silencing speech. These terms are too easily weaponized, enabling those in power to police dialogue and suppress dissent in the name of safety.

By placing excessive pressure on platforms to moderate content, the DSA risks creating an internet governed by fear—fear of fines, fear of bans, and fear of expressing one’s views. If the DSA is allowed to stifle open dialogue and suppress legitimate debate, it will undermine the very democratic principles it claims to protect.

Policymakers must revisit this legislation, ensuring that efforts to regulate the digital sphere do not come at the cost of fundamental freedoms.

Europe’s commitment to freedom of speech demands better. Through our office in Brussels, we at ADF International are challenging this legislation because it’s not up to governments or unaccountable bureaucrats to impose a narrow view of acceptable speech on society.

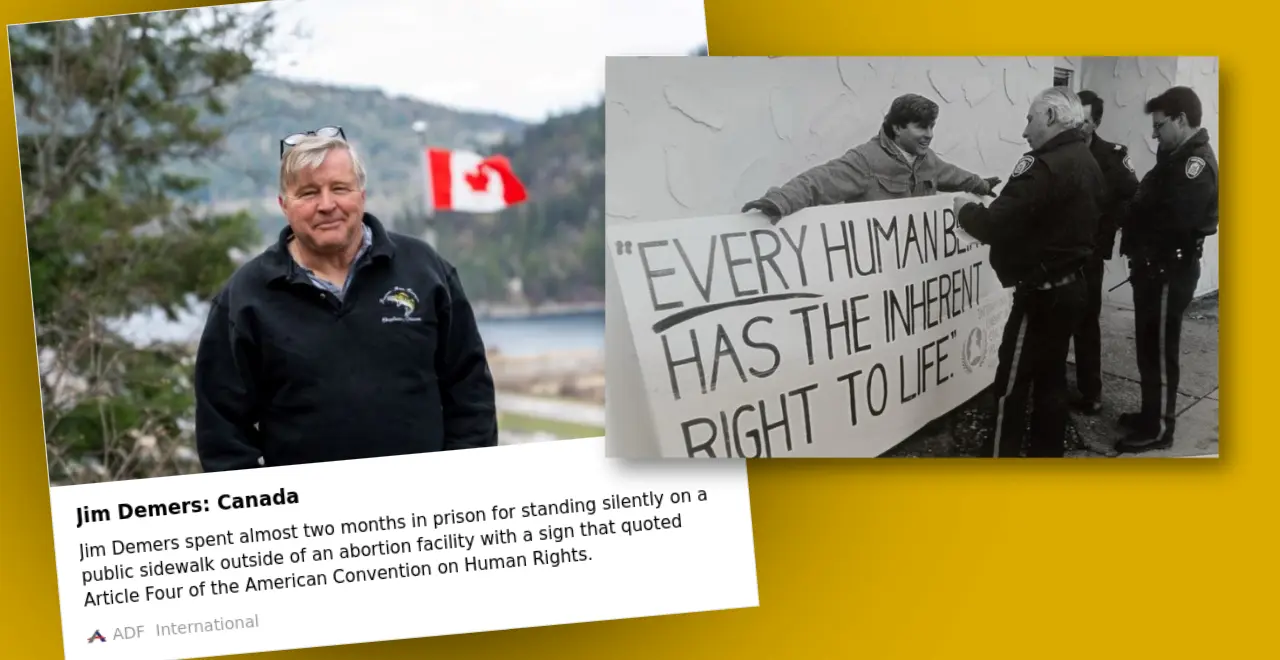

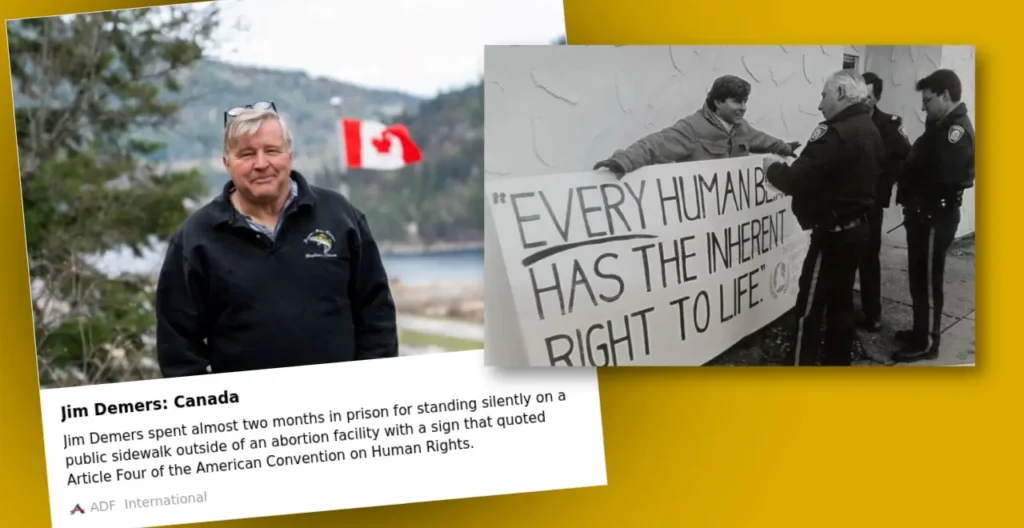

Jim Demers: Justice Delayed and Overdue in Canada

The authorities have violated Canadian man Jim Demers' rights

Executive Director, ADF International

Around the world, governments are enacting so-called “buffer zones”—restricted areas where the state dictates what can and cannot be said. These designated zones—incorporating public footpaths, bus stops, and even people’s homes—prohibit otherwise perfectly lawful activity from taking place within them.

They’re even being used to criminalize silent prayer in public places, as in the cases of Isabel Vaughan-Spruce and Adam Smith-Connor—two courageous UK citizens we’ve stood alongside.

As we’ll see, these restrictions on our lawful right to freedom of thought and expression have been going on for a long time. We want to introduce you to Jim Demers, a lifelong Canadian resident who has faced unrelenting opposition for his pro-life views.

Jim Demers' So-Called 'Crime'

Back in 1996, Jim stood peacefully on a public sidewalk outside an abortion facility in Vancouver, holding a sign that quoted the American Convention on Human Rights:

“Every person has the right to have his life respected. This right shall be protected by law and, in general, from the moment of conception.” This peaceful act of expression led to Jim’s conviction as a criminal. He was imprisoned alongside violent offenders—all for exercising his right to free expression.

His so-called “crime”? Holding a pro-life sign within the “bubble zone” created by the Access to Abortion Services Act of British Columbia. Jim was convicted for “protesting against abortion services” and “sidewalk interference” inside the zone. But Jim didn’t speak to or interact with any members of the public or staff at the abortion facility, nor did he obstruct access to the facility in any way.

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from YouTube. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationCensorship Zones Silence Pro-Life Viewpoints

We can all agree that harassment is wrong. Indeed, in many countries that have introduced these buffer zones, harassment is already illegal. These zones are about silencing pro-life viewpoints in the exact place where a pro-life viewpoint might be needed the most.

Both international law and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms guarantee the fundamental right to freedom of expression. Yet the unjust and discriminatory Act under which Jim was convicted still stands to this day—nearly 30 years later.

The shrinking space for free speech in Canada results from such laws being left to stand for decades, creating the false impression that these restrictions are legitimate. Let us reiterate to you today that they are not.

Jim brought his case to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights in 2004. Twenty years later, the Commission still has not delivered a judgment, choosing instead to simply sit on his case. This is arguably the most severe case of an alleged backlog at any international human rights body.

Conclusion: We Will Stand with Jim Demers and He Deserves Justice

Now, we are standing with Jim. We have reactivated his case and are calling on the Commission to finally rule that Canadian authorities violated his rights. This case isn’t just about Jim—it’s about protecting the freedom of every person to express themselves without fear of criminal prosecution.

If international law and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms mean anything, then Jim’s rights—and the right of every person to free expression—must be defended.

“I hope I’m never silent when bad things are happening, and I hope nobody else is silent either when bad things are happening. I have dedicated my life to speaking out in defence of the unborn, and because of this, I was criminally convicted and even spent time in jail.” Jim’s courage reminds us that silence is never an option when freedoms are at risk. He deserves justice, no matter how delayed.

Facebook’s Commitment to Winding Back Censorship

Practice what you preach, allow free speech

After we – and many other free speech groups – spent years sounding the alarm on the suppression of open conversation online, Mark Zuckerberg has this week committed to winding back censorship across all Meta platforms – including Facebook, Instagram, and Threads.

In a monumental announcement, the CEO admitted that the third-party “fact-checkers” employed to moderate content on Meta were “too politically biased”, and that it’s “time to get back to our roots around freedom of expression.”

This isn’t just good news for Instagrammers and influencers. It marks a sea change in the public landscape, indicating an expectation that our right to free speech will be honoured—whether on or offline.

We can celebrate this important milestone and will be watching closely to see if Zuckerberg follows through on his promises. But at ADF International, we’re still keenly aware that the threat to free speech comes not only from privately run internet platforms but also from governments.

Our Cases of Online Censorship

Take Päivi Räsänen. This Finnish member of parliament will soon be heading to a criminal trial at the Supreme Court because of a Bible-verse tweet she posted in 2019. It wasn’t a social media platform that censored her Christian view—it was the state authorities. The case is due before the Finnish Supreme Court this year.

Or take Chris Elston, a.k.a viral internet sensation Billboard Chris. Last February, he posted about his disapproval of the WHO’s selection of an infamous transgender activist to be on a panel setting guidelines for global transgender policy.

It wasn’t a social media platform that decided that his opinion shouldn’t be heard—it was the Australian authorities. We’re supporting his fight for free speech as he goes to court in March, alongside “X,” who wants to be able to host his viewpoint without government interference.

It’s easy to become discouraged as we live through an era where speaking the truth can land you in legal trouble. But this week, we mark yet another clear indication that we’re moving the needle in the right direction.