- Senator Eduardo Girao & Members of the Chamber of Deputies Marcel Van Hattem, Adriana Ventura, Gilson Marques & Ricardo Salles claim violations of their free speech rights following persistent state censorship in Brazil, including 39-day ban on X (Twitter) ahead of elections.

- ADF International, representing legislators before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, petitions international body to condemn Brazilian censorship and uphold free speech.

Left to right: Senator Eduardo Girao, Members of the Chamber of Deputies Marcel Van Hattem, Adriana Ventura, Ricardo Salles and Gilson Marques.

WASHINGTON, DC (20 December 2024) In light of the ongoing state-driven censorship crisis in Brazil, five Brazilian legislators, including Senator Eduardo Girao and members of the Chamber of Deputies Marcel Van Hattem, Adriana Ventura, Gilson Marques, and Ricardo Salles, are challenging the violations of their free speech rights before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, represented by ADF International.

The Commission has jurisdiction over Brazil as a State Party to the American Convention on Human Rights. The American Convention robustly protects freedom of speech, including prohibitions on prior restraint (censoring expression before it has occurred) and special protections for political speech. Article 13 protects the “right to freedom of thought and expression” which includes “the freedom to seek, receive, and impart information and ideas of all kinds… through any other medium of one’s choice… The exercise of the right…shall not be subject to prior censorship… [and] may not be restricted by indirect methods or means, such as the abuse of government or private controls … or by any other means tending to impede the communication and circulation of ideas and opinions.”

The legislators claim violations of their rights under the Convention, including their freedom of expression and the equal protection of the law, as a result of escalating state censorship, dating back to 2019, which recently reached a head with the X (formerly known as “Twitter”) ban.

In their legal challenge now filed with the Commission, the legislators note that state-sponsored censorship, including the 39-day ban of X, is “disproportionate and of dubious legal basis” and “has affected the conventional rights of the Victims in a direct, particular, and serious way.”

The petition goes on to say that the country’s X blockade “violated the rights of more than twenty million people in Brazil who are users of the platform, having prevented them from accessing the dissemination and reception of information during that time.”

Julio Pohl, ADF International’s lead legal counsel on the case, stated: “The world watched as Brazilian authorities blatantly clamped down on the free speech rights of over 20 million Brazilians by shutting down X ahead of the national elections. While the ban was eventually lifted, the fact remains that millions of Brazilians, including the five legislators now taking their case to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, were subjected to unlawful censorship during a critical time in their country. Censorship has no place in a free society, and it’s time for the Commission to intervene and condemn the vast and ongoing violations of free speech being perpetrated by Brazilian authorities.”

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from YouTube. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationJulio Pohl & Marcel van Hattem

Marcel van Hattem, member of the Chamber of Deputies for Brazil and one of the legislators who filed the petition, commented:

“What we have seen time and again in Brazil is an egregious silencing of political voices, citizens, journalists, or anyone else who might share different viewpoints from Judge Alexandre de Moraes or others in control. This is a major violation of all Brazilians’ free speech and expression rights. We can’t afford to lose Brazil to authoritarianism, which is why I am taking my case to the international level with the help of ADF International. These attempts to silence and censor cannot be allowed to stand.”

Eduardo Girao, Senator for Brazil and party to the petition, stated:

“Brazil is facing a very serious censorship problem. While our constitution protects our rights to speak and express ourselves freely as citizens of Brazil, Brazilians throughout the country are afraid to share their beliefs for fear of persecution and punishment. We must push back against censorship in our country, and it is my hope that the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights will fulfill its obligation to condemn the human rights violations that are taking place in our country.”

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from YouTube. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationJulio Pohl & Eduardo Girao

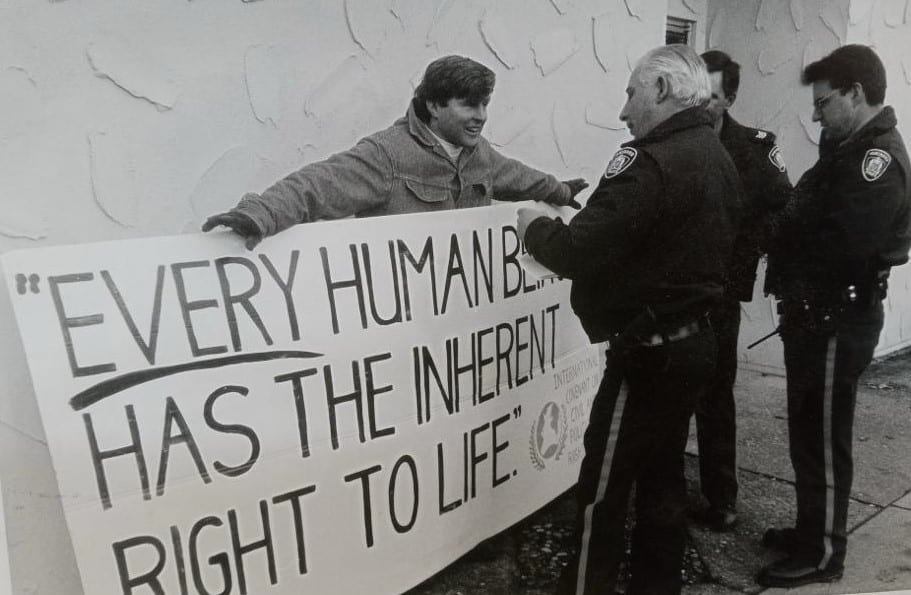

State-sponsored censorship

Censorship in Brazil has been a persistent and escalating problem in Brazil since 2019. The state has targeted conservative voices, including blocking pro-life messages during the 2022 election campaign, which contained views contrary to the pro-abortion position held by then-candidate Lula da Silva.

On 30 August 2024, Justice Alexandre de Moraes of the Brazilian Supreme Court ordered the “immediate, complete and total suspension of X’s operations” in the country after the platform refused to comply with government orders to shut down accounts which it had singled out for censorship. The ban was in effect for 39 days.

ADF International petitioned the Commission to urgently intervene, stating, “The blocking of X in the country is symptomatic of an endemic problem…it has dragged on for more than six years and has caused real damage to Brazilian democracy, producing a chilling effect on the majority of the population who, according to recent surveys, are afraid to express their opinions in public.”

Elon Musk thanked ADF International for its intervention.

In September, over 100 global free speech advocates – including former UK Prime Minister Liz Truss, journalist Michael Shellenberger, five US Attorneys General and Senior UK, US, European and Latin American politicians and professors united in an open letter to call for free speech to be restored in Brazil.

Even with the lifting of the X ban, the state of censorship in Brazil remains severe.

Left to right: ADF International legal counsel Julio Pohl, Chamber of Deputies member Marcel van Hattem, Senator Eduardo Girao, & ADF International Director of Advocacy for Latin America, Tomás Henríquez

Images for free use in print or online in relation to this story only.