- In December, the European Commission fined X €120m under the Digital Services Act, an online censorship law

- X is challenging the fine at the General Court of the European Union, with the support of Alliance Defending Freedom International

- Landmark case is first ever legal challenge of a fine imposed by the DSA

Luxembourg (20 February 2026) – X this week launched a landmark legal challenge against the €120 million fine it received in December under the Digital Services Act (DSA), an EU censorship law.

The social media company filed an appeal against the fine at the General Court of the European Union (GC), a part of the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU), which hears high-stakes challenges to EU regulatory and enforcement actions.

Filed on Monday 16 February, in X v. the European Commission, X argues that the fine violates its right to due process and suggests a prosecutorial bias.

X is challenging the fine, which was issued by the European Commission on 5 December 2025—and for which its owner Elon Musk is also personally liable—with the support of free speech legal advocacy organisation Alliance Defending Freedom International.

This landmark case is the first ever legal challenge of a fine imposed by the DSA, an EU law adopted in 2022. The DSA is a legally binding framework that gives the Commission authority to enforce so-called “content moderation” on “very large online platforms,” like X, Meta, and Google (platforms with more than 45 million users per month), which operate or are accessible in the EU. Platforms that fail to comply with the DSA face massive financial penalties and can even be suspended.

The DSA has faced criticism from European and global free speech experts, European NGOs, the US Administration, and the House Judiciary Committee for imposing an online censorship regime around the world.

X and its owner Elon Musk repeatedly have been singled out by Brussels for the free speech stance of the platform, raising concerns that X is being targeted for refusing to implement sweeping online censorship under the DSA.

In its legal challenge against the fine, X argues that the Commission’s interpretation of the relevant obligations, systematic breach of the Applicants’ rights of defence, and of the most basic due process requirements suggest a prosecutorial bias.

This judicial challenge is a landmark case, as it is the first opportunity for the EU court to examine how the Commission calculates DSA fines and whether enforcement of this law respects fundamental rights.

The case also challenges the Commission’s combined role as regulator, prosecutor, and judge under the DSA—a role codified in the DSA itself, but which raises high concerns for due process and the rule of law.

Because the DSA applies to “very large online platforms,” a ruling from the EU court will affect how all big tech platforms are regulated by the law.

In its legal challenge, X argues for the fine to be withdrawn. If relevant aspects of the DSA legislative instruments are found to not be compliant with other EU law, specific provisions in the legislation could also be annulled.

Other big tech companies, as well as EU institutions and EU Member States, could join X in the legal challenge in the future, under Article 40 of the Statute of the CJEU.

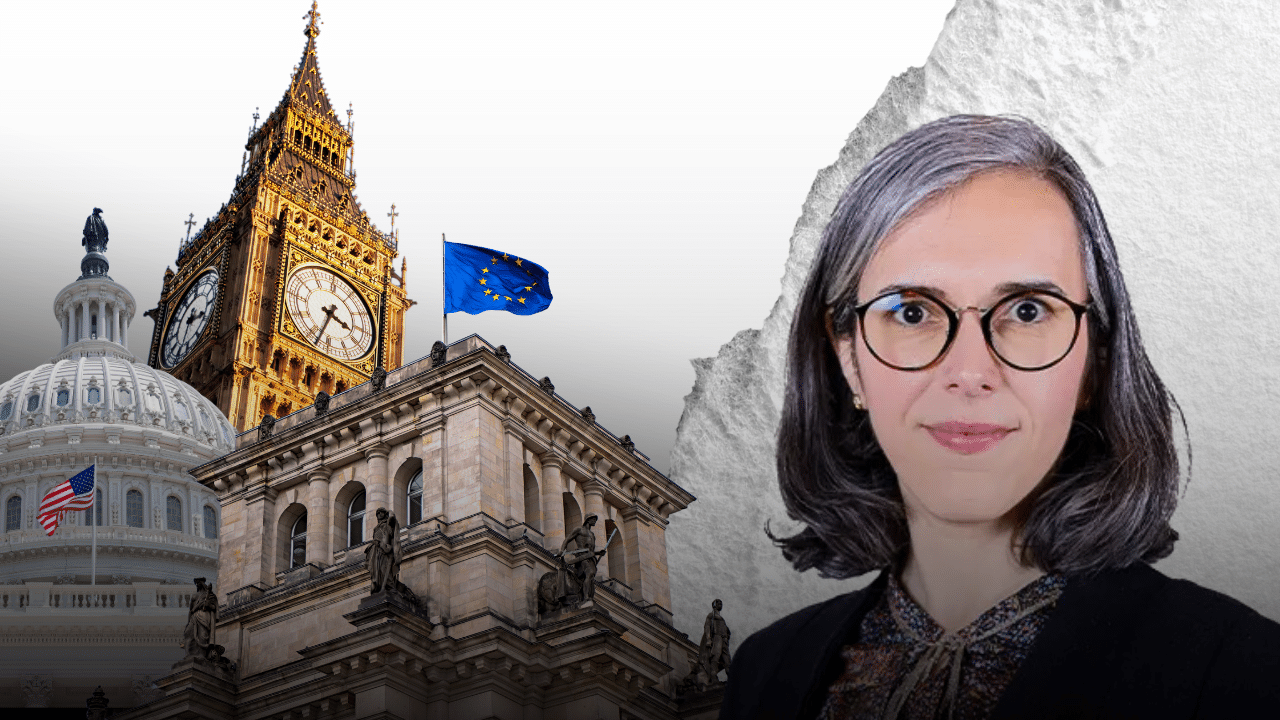

Brussels-based lawyer Dr Adina Portaru, Senior Counsel, Europe for ADF International, said:

“X is being targeted by the European Commission because it is a free speech platform. Social media platforms are today’s public square, and the DSA threatens speech in that public square.

“X is where millions of people go to freely express their views. This is a crackdown on X by authorities who view a free speech platform as a serious threat to their total control of online narratives. By targeting X, they are targeting the free speech of individuals across the world who simply want to share ideas online free from censorship.

“It’s no surprise that the company and its owner Elon Musk were landed with the first ever DSA fine.

“This case turns on whether the enormous powers given to the European Commission under the DSA are compatible with the rule of law. Under the DSA, the Commission is able to define the rules for so-called ‘content moderation,’ launch investigations, enforce them, and impose massive penalties for noncompliance, all with no meaningful checks and balances. The threat to free speech is severe.

“If the Commission’s concentration of power goes unchallenged, it will further cement a highly problematic standard for speech control across the EU and beyond.”

In an online statement, X said:

“X filed an appeal at the General Court of the European Union challenging the €120 million fine imposed by the European Commission on 5 December 2025, the first non-compliance fine under the Digital Services Act (DSA).

“This EU Decision resulted from an incomplete and superficial investigation, grave procedural errors, a tortured interpretation of the obligations under the DSA, and systematic breaches of rights of defence and basic due process requirements suggesting prosecutorial bias.

“This landmark case is the first judicial challenge to a DSA fine and could set important precedents for enforcement, penalty calculations, and fundamental rights protections under the 2022 regulation. X remains committed to user safety and transparency while defending our users’ access to the only global town square.”

Background on the DSA fine

According to the Commission, the December 2025 fine was issued for alleged breaches of transparency and procedural obligations under the DSA. X denies these allegations.

X has been subject to censorship pressure from the Commission since even before the DSA came into law.

In response to X’s withdrawal from the voluntary Code of Conduct on Disinformation, Thierry Breton, former European Commissioner, stated: “Twitter leaves EU voluntary Code of Practice against disinformation. But obligations remain. You can run but you can’t hide. Beyond voluntary commitments, fighting disinformation will be legal obligation under #DSA as of August 25. Our teams will be ready for enforcement.”

Additional DSA investigations by the Commission are ongoing against X, including for alleged failure to combat “false information and illegal content”. These could result in further fines in the future.

Under European legislation, “illegal content” includes a plethora of draconian anti-free speech and “hate speech” laws—for example, in Germany it is illegal to insult politicians online.

X’s legal challenge comes in the context of increased targeting of the platform around the world. French authorities this month raided the social media company’s offices in Paris, a Spanish minister raised the possibility of a countrywide X ban, and multiple investigations are ongoing in the UK.

Global free speech concerns with the Digital Services Act

The DSA carries a clear threat of extraterritorial consequences outside of the EU.

A recent report from the US House Judiciary Committee showed that platforms have been pressured into changing their global content moderation rules to comply with the DSA’s censorial standards.

In 2024, prior to his live X interview with presidential candidate Donald Trump, Musk withstood pressure from then EU Commissioner Thierry Breton to censor the interview in line with the DSA. As attempted in the Trump interview, the DSA allows for the takedown of content that originates outside of the EU.