- At House Judiciary Committee hearing, Parliamentarian Päivi Räsänen testifies about her six-year-long criminal prosecution for tweeting a Bible verse under Finnish “hate speech” law.

- An ADF International European legal expert further testified on the dangers of European online censorship, including through the EU Digital Services Act; in addition to Irish comedian Graham Linehan, who testified on his UK arrest for X posts.

WASHINGTON, D.C. (Feb. 4) – Today, experts from Europe delivered a warning to the U.S. Congress about the growing threat of European censorship to American free speech.

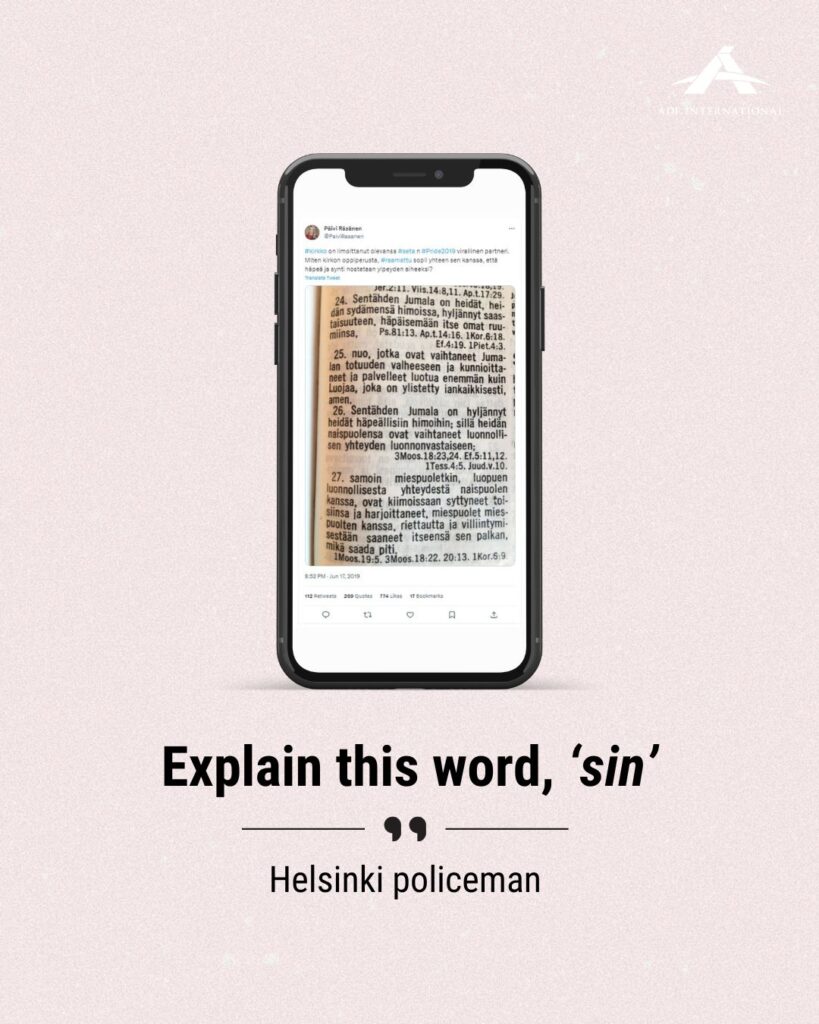

Finnish Member of Parliament Päivi Räsänen addressed lawmakers in a hearing titled “Europe’s Threat to Speech and Innovation: Part II,” hosted by the House Judiciary Committee. In her testimony, she detailed her ongoing criminal prosecution in Finland for expressing her Christian beliefs online, including in a 2019 Bible-verse tweet. Räsänen’s case has become one of the most prominent examples of the criminalization of peaceful speech in Europe.

“Speech that is lawful today can become criminalized tomorrow. This should concern every person that values freedom,” Räsänen said. “My case shows where this path can lead. Recent developments from the European Union, like the Digital Services Act, make European censorship a worldwide concern.”

Prosecuted for over six years under a “hate speech” provision in the section of Finland’s criminal code pertaining to war crimes and crimes against humanity, Räsänen is currently awaiting a verdict from the Supreme Court of Finland. Her legal defence has been coordinated by ADF International.

“When the state controls which ideas and beliefs may be expressed, democracy becomes fragile,” Räsänen added.

“Speech that is lawful today can become criminalized tomorrow. This should concern every person that values freedom. My case shows where this path can lead. Recent developments from the European Union, like the Digital Services Act, make European censorship a worldwide concern."

- Päivi Räsänen

Lorcán Price, Irish barrister and Legal Counsel with ADF International, also testified before the Committee, outlining how the European Union is using online speech regulations such as the Digital Service Act to create a dangerous worldwide censorship regime.

“It is now undeniable that the reach of the DSA is not just a European problem,” Price said in his testimony. “The Commission has fired the first shots in a global struggle over whether people can speak the truth and whether American companies including Google, Bing, and Meta are free to continue to drive Internet innovation or instead be forced to help Europe silence speech worldwide.”

Price warned that the EU’s speech restrictions risk being exported globally, particularly through large online platforms that operate across borders, raising concerns for Americans whose lawful speech could be restricted through foreign censorship.

He cited the DSA’s first major fine of €120 million against X, which was issued in December for alleged violations of transparency and user-protection obligations.

“The enormous fines levied on X by the EU commission proved beyond all doubt that the EU means to strangle free speech by a systematic assault on US companies,” Price said. In his written testimony, he added, “While these penalties are the first that the EU has imposed under the provisions of the DSA, be under no illusions, they will not be the last.”

Graham Lineham, an Irish comedian and writer who was arrested for his X posts in September 2025 in London, also provided a witness testimony on the panel.

Background

The hearing follows a recent report from the House Judiciary Committe previous House Judiciary Committee session on the threat of Europe’s growing censorship, during which Price also testified, warning lawmakers that European censorship laws threaten free expression far beyond the European Union. The initial hearing focused largely on the EU’s Digital Services Act and its implications for Americans’ online speech. Most recently, The House Judiciary Committee warned about the DSA’s risks to American free speech in a new report “The Foreign Censorship Threat, Part II: Europe’s Decade-Long Campaign to Censor the Global Internet and How it Harms American Speech in the United States.”

The DSA grants the European Commission broad authority to regulate content on large online platforms. While framed as an online safety measure, the law creates strong incentives for platforms to remove lawful speech through heavy fines, government oversight, and reliance on “trusted flaggers” to identify allegedly problematic content. Because major platforms operate globally, the DSA risks establishing a de facto worldwide censorship regime that affects users far beyond Europe.

ADF International has been at the forefront of raising concerns about the DSA and defending individuals targeted under Europe’s expanding speech laws, including providing legal support in Räsänen’s case, which has drawn international attention as a warning of the erosion of fundamental freedoms.